Are Target Date Funds Useful In Retirement?

Let’s discuss reasons not to use target-date funds during the retirement drawdown phase.

A fund-of-fund (like a target-date fund) is simple, efficient, and easy to manage during accumulation. Remember, though, that everything changes during de-accumulation.

You can dollar-cost-average into target-date funds and take advantage of the glidepath that gradually dials down market risk. Risk, however, is different in retirement! Sequence of returns risk is much more critical than market risk when retired.

Let’s go over why you want to forget target-date funds in retirement.

What are Target Date Funds?

First, a target-date fund is a fund of funds. It generally includes US stocks, international stocks, and bonds. Many target-date funds can be active or passive and may contain cash, TIPs, and other slices (emerging, REIT, commodities, etc.).

They are most commonly used in defined contribution (401k, 403b) plans; their employer defaults participants into target-date funds. They typically are labeled at 5-year retirement intervals (2020, 2025, 2030, etc.), which indicate the year you are likely to retire. Gradually, they dial back the percentage of stocks in favor of bonds and other safer assets.

Thus, your “risk” (at least as measured by market risk or volatility) decreases as you age. The glidepath is how asset allocation changes over time.

In essence, target-date funds balance growth vs. risk and de-risk over time.

Target Date Funds are for Accumulation, not Drawdown

Target-date funds are specifically designed for accumulation, not for drawdown.

Target-date funds leave much to be desired when withdrawing from your accounts to provide retirement income.

After their expiration (for example, the 2020 fund in 2022), most target-date funds become income funds. Interestingly, income funds are static and very conservative, with only 20-30% in stocks. Therefore, these income funds are not ideal for creating sustainable, stable, and inflation-adjusted income for retirement.

So, in reality, it is not the target date fund you should avoid in retirement; it is what the target date fund becomes!

Target Date Funds can be “To” or “Through”

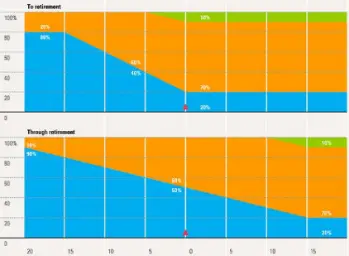

Does your target-date fund go “To” or “Through” your target date?

Both are available, but “through” is the most common. With a “through” fund, the asset allocation gets more conservative even past your retirement date.

Let’s look at some examples:

- Vanguard: Glidepath goes from 40% stocks to 30% stocks the seven years following retirement, then becomes the income fund

- Fidelity: Fidelity continues to get more conservative for 20 years following retirement and winds up with 24% stocks when it becomes the income fund

- T.Rowe: Amazingly, T.Rowe takes 30 years to glide down to 20% stocks!

Compare these “through” plans to a “to” plan that hits the income fund the same year you retire. These types of funds generally become income funds in the same year.

Above, you can see the difference between a “to” and a “through” plan. On the top, a to plan hits a static asset allocation the year you retire (red up-arrow) and never changes. Below, a through plan continues to get more conservative even after the target date.

This enormous variability in target-date funds is reason #1 why you should not use one in de-accumulation. What does your target-date fund even do, and is that right for you?

Too Conservative

Target date funds are just too conservative for many, especially in retirement. Whatever happened to the standard 60/40 portfolio? While it is good to de-risk before retirement, the 20-30% stocks are not enough to outpace inflation over time and provide a stable income for retirement.

Are target-date funds too conservative to be used in retirement? Yes!

Target Date Funds are NOT for your Brokerage Account

To be clear, target-date funds may be okay for accumulation in your employer plans (pre-tax), but they should not be used in Roth or brokerage (after-tax) accounts.

In Roth accounts, you have many other better options for accumulation and de-accumulation.

For brokerage accounts, please do not use target-date funds! You might have a low basis position here, meaning you must pay capital gains when you sell the funds. And you do not want target-date funds causing an increasing amount of ordinary income every year, yet you cannot sell it due to the embedded capital gains! In addition, bonds (and thus target-date funds) should be in your pre-tax accounts rather than your brokerage account due to tax considerations (also known as asset location).

Target-Date Fund Problems During Withdrawal Phase

During your withdrawal phase (retirement), you sell investments to create income. Ideally, you would like to sell your best-performing asset and not sell stocks when they are down.

Since target-date funds rebalance daily, you are always de-risking when the market trends up and de-risking overtime via the glidepath.

When you sell investments to create income, however, you have to sell both the stocks and the bonds when you sell shares of your target-date fund. If the market is down when you take a withdrawal, you are selling stocks when they are low, thus locking in the losses.

Some consider this a benefit of target-date funds, as they automatically rebalance for you. However, outside of a target date fund, if stocks are down and you sell bonds to create income, you still rebalance your account to your desired asset allocation. So, either way, you wind up selling stocks to get your risk level (asset allocation) back into shape.

But let’s dive deep into why that is not true. Here is the special bonus reason you should not have target-date funds in retirement.

Top Reason to Not Have Target Date Funds in Retirement

This is a bit complicated but stick with me because this is the top reason for not having target-date funds in retirement.

This idea starts with rebalancing. How often should you rebalance your accounts, and does that change in de-accumulation?

There is debate about how often you should rebalance during accumulation, but I suggest that every 1-2 years is frequent enough. This allows you to participate in a momentum tilt without getting too far outside your desired asset allocation (and thus the amount of risk you are willing to take during accumulation). Remember, you don’t rebalance during accumulation because it gets you more return. You rebalance because it reduces volatility (market risk).

Next, how often should you rebalance in de-accumulation?

Risk is different in de-accumulation. The risk is not one of market risk; it is sequence of returns risk. The idea here is that a bad sequence (over a few years), while you withdraw from your accounts, you can unleash a portfolio death spiral if you sell your assets when they are low, thus locking in the losses.

Rebalancing in de-accumulation has less to do with mitigating market risk and more with mitigating sequence risk.

Please stick with me for a second. If you sell your target-date fund (which rebalances daily) during a market correction, you will be fine if the market goes up afterward. But during a bad sequence, the automatic (daily) rebalancing of the target date fund leads you to continually sell stocks when they are down. You sell stocks when they are down yearly or month after month.

On the other hand, outside of a target-date fund, you might sell only bonds when the market is down. You don’t need to rebalance; you can see what happens the following year in the market. If it is still down, you can continue to sell “safer assets” during subsequent down years and not get trapped by sequence of returns risk. Here, you never sell stocks when they are down and don’t rebalance into the teeth of a poor sequence.

Reasons to Skip Target Date Funds in Retirement

In summary, don’t use target-date funds in retirement.

During accumulation, they may be appropriate for your pre-tax accounts (but not your Roth or brokerage accounts) if you have no better alternatives. Indeed, they may be the best choice in your 401k before separation.

However, target-date funds, such as de-accumulation or retirement, are not indicated during the withdrawal phase. So, you are better off separating your stocks and bonds and selling the winners. Don’t sell the losers and lock in paper losses, especially during retirement.